MWD61 - On Information and Identity

Or why none of the things we hope might work is likely to convince people to change their mind

Welcome to Midweek Dinner. There’s a whole story behind that name, something about the way Wednesday creeps up on you, and you have to cobble together a meal out of whatever you can scrounge from the fridge. And yes, sometimes there is talk of food in this place. But mostly it’s about what I’ve been reading, in print and online; or what I’ve been thinking, in clarity and confusion; or what I am hoping, in fear and in joy. And you are always invited to join in.

—— The best conversations take place around the dinner table. — —

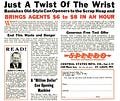

About a month ago, I retweeted this tweet from musician Drew Holcomb:

Since then, I’ve seen multiple variations of this Very Online Exhortation, all urging their audience (who probably regularly wear a mask) that wearing a mask is SO EASY EVEN A CHILD CAN DO IT.

What are we doing when we share these messages? Let’s break down our options.

Option One

We hope our freedom-from-masks neighbor or family member will be ashamed that they are unable to do what children can do easily and therefore, change their stance on masks.

While shame can change behavior, it requires a few key components (explained in this Scientific American article):

the person must believe they have transgressed a norm

the transgressor must believe the norm to be valid and desirable.

In this case, the norm being expressed by the tweet-er (that grown-ups should behave with greater maturity than children, especially in the face of difficulties) is not something the non-mask-wearer is likely to disagree with; however, they do not see the mask issue (or themselves) in this light. If they believe masks to be an oppression or manipulation, this example proves them right. The children here are immature, sheep being led astray by a failing shepherd. They need feel no shame, so this option fails.

Option Two

I asked my brilliant friend Garrett Bucks about a similar tweet of his, and this is how he replied:

What I hope it does is give a little oxygen to the broader project of nascent American collectivism. In general, folks who really do hope that we can be a more caring, less cruel society are often (understandably) super beaten down by all the counter-evidence of our societal cruelty. And while evidence of kids being kind isn’t as compelling, perhaps, as evidence of adults being kind, it’s still really lovely and wonderful evidence.

While I don’t doubt Garrett’s intentions at all, when I look back at my own retweet, especially that part about “much to learn from our children,” I’m left thinking something darker. Which brings us to

Option Three

Even though we might resist the notion of social media as echo chamber, we know it’s mostly true. So, when we tweet something like this, are we doing anything more than just assuring ourselves (and our audience) that we’re on the right team? That we are the good guys, and those other, immature bastards who refuse to wear a mask? Well, we are not them.

As cynical and mean-spirited as option three sounds, I think it is the closest to the truth, both about myself and Drew Holcomb and the like and about persuasion and information-seeking and the ways it is all wrapped up in our perception of ourselves.

In her textbook Information and the Information Professions, Marcia J. Bates notes that

Information seeking makes one vulnerable. Information, by many definitions, is surprise. Not all surprises are fun or desirable. Therefore, the seeker opens him or herself up to risk, to the potential need to reorganize or reorient his or her hard-earned knowledge. The consequences of this risk ripple throughout the behavior we call information seeking. The behavior ranges all the way from avoiding information to actively seeking it out in cases where our lives are on the line or our passions are engaged with a fascinating subject.

In a later chapter, she cites Brenda Dervin’s sense-making model before concluding

If “we are what we know,” if our sense of self is based, in part, on our body of knowledge of the world, then to change that knowledge may be threatening to our sense of self.

I think Bates is absolutely right to include “avoiding information” on her continuum of information-seeking behaviors. I would add “only accepting information that aligns with our existing opinion” to her list. Our opinions on any given subject, however, are less important than our “sense of self.” Consider the following survey question (will anyone on Twitter believe this is an actual survey? We’ll see.)

The easy assumption is that even though we know we are flawed, we see ourselves —generally speaking — as good. Our susceptibility to misinformation comes into play when to change our opinion on an issue would mean admitting we had been on the wrong side. Garrett notes this difficulty when it comes to walking with white people through issues of race:

We’ve never had more information available to us, as white people, that something is intensely wrong with the system. . . . it can cause an incredible moment of cognitive dissonance: there’s this moment when you realize, oh, I thought I was a good person, and I’m trying to be a good person, and it feels really crappy to internalize this idea of “oh, I’m on the wrong side.”

The key, I think, to overcoming that cognitive dissonance is to separate yourself from the identity labels that can so often rule and define you. And that, friends, is where I land on the kids and masks thing.

Kids are still molding the play-doh of their identities. They are governed primarily by the authority figures in their lives, the ones telling them to wear a mask (or don’t), to drink a soda (or don’t), to go to church (or don’t), to match their clothes (or don’t!). Mostly, they don’t get to decide, so they can wear their masks without feeling like it somehow defines them. It doesn’t tell the world anything about who they are.

It also doesn’t help to use kids and their ease with masks as a method of persuasion because as adults, we are all too aware of the ways wearing a mask (or not) signifies our affiliation with the “right side.” The only thing that might convince an information-avoidant person is evidence that maintains or reinforces their in-group status.

Of course, the real work lies in breaking down the rigid boxes we’ve so willingly installed ourselves in. For me, it’s not an issue of masks or vaccines. But there are likely ways that my sense of self keeps me from embracing some greater truth or goodness. The trick is figuring out how to actually see yourself fully enough and humbly enough to try to change. That, too, is real work. In both cases, however that work gets done, it likely won’t happen on Twitter.

Thanks as always for reading and thinking with me. If you have thoughts to share, just hit reply! I welcome your conversation and promise a response.