MWD58 - On the Stories We Tell Ourselves about Ourselves

Or what happens when we assume we are the main character

Welcome to Midweek Dinner. There’s a whole story behind that name, something about the way Wednesday creeps up on you, and you have to cobble together a meal out of whatever you can scrounge from the fridge. And yes, sometimes there is talk of food in this place. But mostly it’s about what I’ve been reading, in print and online; or what I’ve been thinking, in clarity and confusion; or what I am hoping, in fear and in joy. And you are always invited to join in.

—— The best conversations take place around the dinner table. — —

“It’s not personal.”

“It’s not about you.”

“Maybe you’re not the main character of that story?”

These are things I have said — to my teenagers but more often to myself — countless times. It helps me, a person with tendencies toward selfishness and navel-gazing, to erase myself from the narrative or at least set myself outside the narrative, rightly reminded that I am little more than an extra in the scene. I fail at it regularly, forcing myself into the spotlight or diminishing the star power of those around me. But when it works, it changes everything: I realize that the person who “cut me off” almost certainly didn’t see me or that the way my kid snapped at me is likely bubbling out of a stew of emotions unrelated to me.

My friend Beth Kephart is a brilliant writer and a generous friend. And this piece on memoir as a conversation is one of the many fine things she has created, urging memoirists to

Write toward the world and not just toward themselves.

She goes on to explain, “when memoirists conceive of themselves as conversationalists in search of understanding … when they profess an interest in exploring the greater meaning of the shared human condition … both the writer and the reader gain.”

Even in telling our own stories, she insists, we should keep in mind the possible stories of our readers.

Maybe the heart of it comes from that act of curiosity — being “in search of understanding” as an act of decentering ourselves? L. M. Sacasas, in writing about Outsourcing Virtue, might agree, pointing his readers to Ivan Illich who questions our reliance on technological systems to outsource our good deeds [I could do a whole rant on Meal Trains here, but I will refrain.] He argues,

if you forget the particular, bodily, situated context of the other, then the freedom to do good by them … can become the imperative to impose the good as you imagine it on them.

When we see ourselves as the main character, we view the world through our lenses, seeing “the good as you imagine it” as universal. We assume that our wants are right and good, so we offer others what we most desire. When we do, however, the person we are trying to help or support or love might repeat those same statements, but in a different light, one loaded with hurt feelings:

“It’s not personal.”

“Whatever this is, it’s not about me.”

“I’m not the main character in this story.”

===

To pivot, and perhaps unexpectedly: consider George Packer’s “The Four Americas” in the July/August 2021 issue of The Atlantic (published online as “How America Fractured into Four Parts”). In this long excerpt from Packer’s new book, he presents the United States as a blend of four sections that he names Free America; Smart America; Real America; and Just America. But before he breaks all that down, he writes,

the most durable narratives are not the ones that stand up best to fact-checking. They’re the ones that address our deepest needs and desires. … Nations require more than facts — they need stories that convey a moral identity.

Compelling idea, but the question is: Whose deepest needs and desires and whose moral identity gets to be the protagonist, the character around which the narrative is shaped? We are a nation of individuals, a nation built on the narrative of individual exceptionalism; but we have also always been a united nation of disparate parts.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about freedom and goodness, both individual and collective. I remain convinced it has to be both. We have to be individuals with unique needs and desires and we have to be willing and able to set those aside in favor of the collective at times. There might be four americas, but they don’t have to be at war. We contain multitudes.

The truth is, no matter how much we might try to quiet that part of ourselves, we are always the main character in our own story. That’s not wrong. We’ve all driven into a sunset on a perfect night, windows down and music up, the soundtrack of our lives unspooling around us. So maybe the idea is less about what role you play in the story and more about how much attention you give to the stories all around you. Maybe, it’s not about being the main character or a sidekick; it’s about being a reader, willing to carry multiple strands of narrative at once, infinitely curious about what will happen next.

A few more things to think about:

— This Vox piece from Kelsey Piper introduced me to a new terminology (degrowth) for some ideas I’ve been swimming in for awhile. What I love about the article, however, is how thoughtfully Piper challenges this view that I might ordinarily agree with. I can agree with the central tenet (that we have to do more and faster) and also want to read Jason Hickel’s Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. I can understand how reducing consumer purchasing (especially of cheap, disposal goods) in developed countries could have harsh consequences in the developing countries that produce those goods and also think fighting for longer-lasting products is the right choice. Where I would quibble with Piper is the stance that our ethical responsibility to those in developing countries should somehow take priority over a commitment to sustainability. Moving away from coal-powered electricity (and thus reducing or eliminating coal mining as viable employment) has decimated the economies of Appalachian communities. We can see the damage it has done and still know it is the right thing to do. So, why should we not view $3 t-shirts and disposable cell phones the same way? Still, I love that the article has me thinking about multiple approaches to the problem, allowing me to hold contrasting truths in my head at once.

— I have a longtime friend who counts among his longtime friends the inimitable Garnette Cadogan, who I had heard stories about long before I read his amazing “Walking While Black.” Recently, I came across this shared walk via Isaac Fitzgerald, and I particularly love this about walking at night:

The very atmosphere feels more ready to accommodate you. Many places have one, singular, ingrained core story during the daytime, but at night? At night, these places give up many stories. A multiplicity of stories waiting to reveal themselves to you.

— On the subject of walking, this Brain Pickings piece on Walking by Thomas Bernhard quoted this passage, and it is perplexing and knotty and so good:

Looked at in this light, all concepts (ideas)… like self-observation, self-pity, self-accusation and so on, are false. We ourselves do not see ourselves, it is never possible for us to see ourselves. But we also cannot explain to someone else (a different object) what he is like, because we can only tell him how we see him, which probably coincides with what he is but which we cannot explain in such a way as to say this is how he is. Thus everything is something quite different from what it is for us… And always something quite different from what it is for everything else.

— Cat Valente has a new novella up on Tor.com, and I have only just begun to fall in love with it after learning it is a retelling or Orpheus and Eurydice and also this:

All he’d ever needed to do was sing and the world opened itself up to him like a jewelry box—and she was there when it did, the little pale dancer on the velvet of his ease, spinning inexorably round and round on one agonizingly perfect, frozen foot. If the world declined to open for others, that did not concern him.

Unexpected Joy Department:

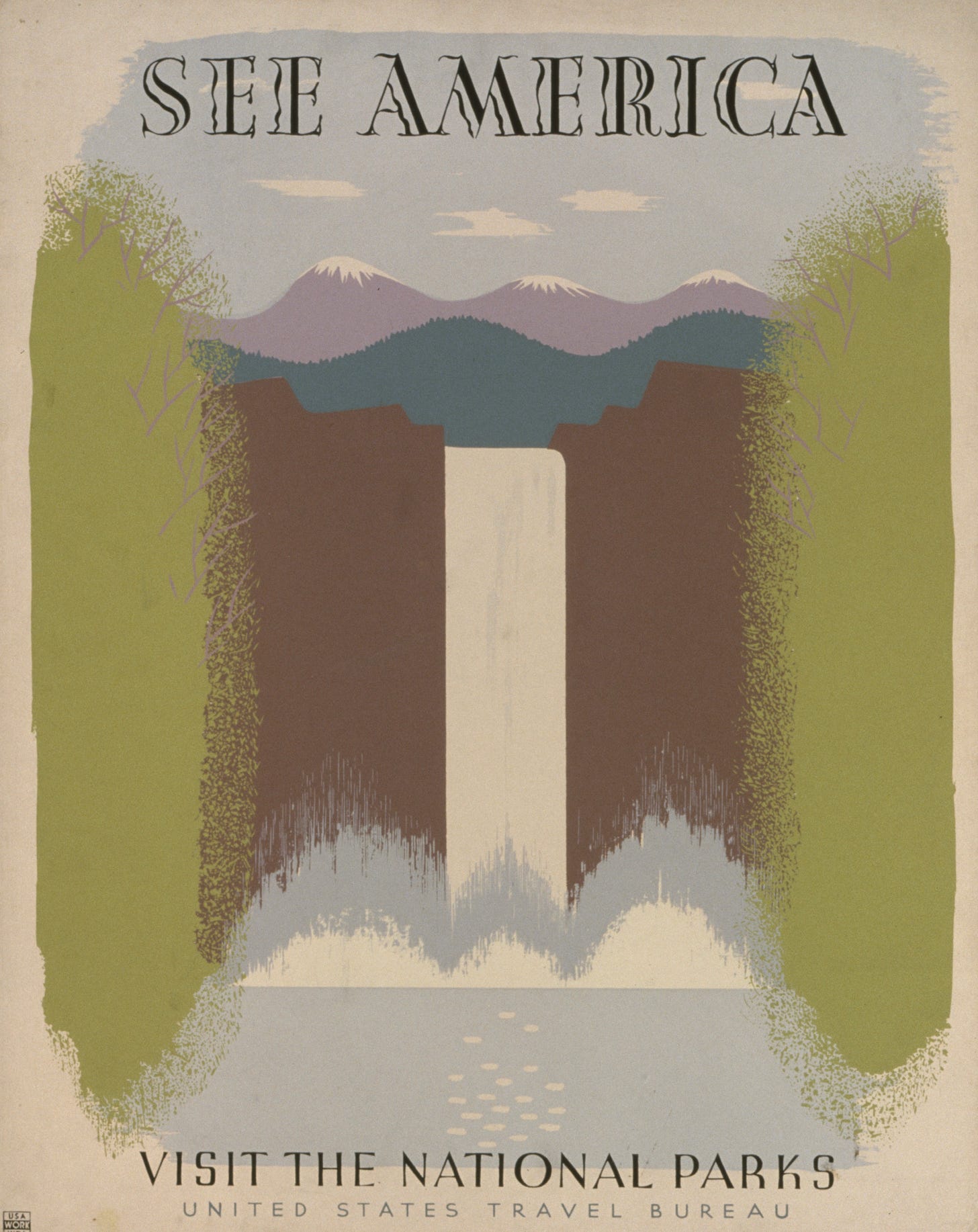

These gorgeous travel posters are available from the Library of Congress - free to use and reuse - and I am in love. Also: cats, hats, and not an ostrich.

Thanks as always for reading and thinking with me. If you have thoughts to share, just hit reply! I welcome your conversation and promise a response.